New global survey reveals opportunities to address organ damage risk with people living with lupus earlier in the course of their disease

Issued: London, UK

For media and investors only

- Survey examined healthcare professional approaches to preventing organ damage – which impacts many people living with lupus within five years of diagnosis

- HCPs report that COVID-19 pandemic caused delays in diagnosis and care

- Findings also point to challenges in identifying risks and measuring disease activity

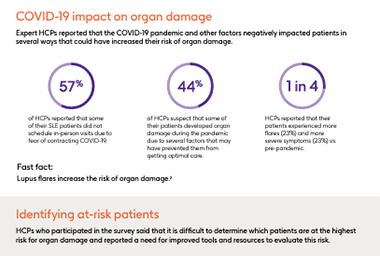

In findings from a new global survey, nearly half (44%) of the expert healthcare professionals (HCPs) surveyed across seven countries reported that the COVID-19 pandemic and other factors prevented some people living with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) from getting optimal care in the past two years, increasing their risk for organ damage.

Organ damage, which occurs most commonly in the kidneys, skin, and heart,1 is a key determinant of poor long-term prognosis in SLE.1 Delays in care – such as those experienced during the pandemic as reported by survey respondents – can be critical, as organ damage can occur in up to 48% of people living with lupus, most within five years of diagnosis.2 Lupus flares can also increase the risk of organ damage, and some surveyed HCPs report that nearly a quarter (23%) of their patients experienced an increase in flares compared to pre-pandemic.

The survey of 648 rheumatologists, nephrologists and internal medicine specialists offers global insight into the range of factors that, in addition to the pandemic, contribute to the increased risk some lupus patients have for developing organ damage, such as lupus nephritis, an inflammation of the kidneys that can lead to kidney failure and is one of the most common complications of SLE.3

While surveyed HCPs are familiar with the risk of organ damage and how fast it may occur in lupus patients, they also cited challenges in determining which patients are most at risk for organ damage: 79% want more effective ways to measure disease activity, and four in five (80%) want an easy way to identify which patients are at significant risk for organ damage.

Dr. Rajeev Raghavan, nephrologist, HCA Houston Healthcare said: “Organ damage is a very real risk for people living with lupus and these survey results underscore the critical need for improved tools and guidelines. It’s also important that we, as treating physicians, educate our lupus patients about the risk of organ damage at the time of diagnosis and work together to create a long-term disease management plan that actively reduces organ damage risk.”

The need for better ways to predict and monitor organ damage may explain why some surveyed HCPs said they wait to talk to their patients about these risks. Nearly half of HCPs (46%) said they only discuss the risk of organ damage once patients present with organ damage symptoms, and 65% typically wait more than a year after diagnosis before discussing the potential for organ damage with patients.

Mike Donnelly, Vice President of Communications, Lupus Foundation of America (Secretariat of the World Lupus Federation) said: “Some of these findings echo what we know about the experiences of people with lupus and organ damage. These important conversations are happening between people with lupus and their doctors, but more action is needed and should be happening at diagnosis if we are going to truly reduce the burden of organ damage on people with lupus and their families.”

According to the survey, more information about available treatments might help HCPs and patients to consider long-term treatment plans, balancing the need for rapid symptom relief with long-term treatment goals:

- Most HCPs (78%) say that data showing the benefits of different therapies for patients at risk of organ damage would be helpful.

- Most (72%) HCPs say that the current standard of care (SOC) regimen (anti-malarial medicines, steroids and immunosuppressants) can sufficiently reduce the risk of long-term organ damage for most lupus patients. However, research shows that standard of care (SOC), which includes anti-malarial medicines, steroids and immunosuppressants, does not prevent organ damage in a significant number of patients and in fact, steroids may actually contribute to it.4,5,6,7

- Three in four (79%) HCPs surveyed say that a lack of disease-modifying therapies makes it difficult to treat lupus, though separate research shows symptoms of lupus can be managed by disease modifying treatments that disrupt the inflammatory process.8

Dr. Roger A. Levy, GSK Global Medical Expert, Immunology & Specialty Medicine said: “Lupus can be better managed with early diagnosis and expert medical care, but organ damage affects many people living with lupus within five years of diagnosis. The survey results highlight that, as we emerge from the pandemic, there are critical opportunities to drive proactive conversations about organ damage risk and how to align the short and long-term treatment goals. We are committed to ongoing research and scientific exchange on a proactive approach to lupus care.”

About the survey

The global HCP survey was conducted by Material on behalf of GSK between July and September 2022 among 648 HCPs across seven countries—Canada (n=41), China (n=100), France (n=102), Germany (n=102, Japan (n=100), Spain (n=100) and the United States (n=103).

The survey was designed to explore the attitudes and practices of HCPs in the treatment of their patients with SLE, including those with lupus nephritis (LN), with a focus on topics related to disease modification in lupus, as well as organ damage.

Surveyed HCPs had a primary specialty of rheumatology, nephrology, or internal medicine, were board certified in their specialty and managed the treatment of SLE patients, including those with LN:

- HCPs in the US had a minimum of 15 SLE patients

- HCPs in Canada, China, Germany, and Spain had a minimum of 10 SLE patients

- HCPs in Japan and France had a minimum of 5 SLE patients

The HCPs were not employed or under contract with pharmaceutical companies, healthcare manufacturers, or government regulatory agencies.

Results of any sample are subject to sampling variation. The magnitude of the variation is measurable and is affected by the number of interviews and the level of the percentages expressing the results. In this particular study, the chances are 95 in 100 that a survey result does not vary, plus or minus, by more than 9.7 percentage points from the result that would be obtained if interviews had been conducted with all personas in the universe represented by the sample. The margin of error for any subgroups will be slightly higher.

About systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), the most common form of lupus, is a chronic, incurable, autoimmune disease associated with a range of symptoms that can fluctuate over time including painful or swollen joints, extreme fatigue, unexplained fever, skin rashes and organ damage. In lupus nephritis (LN), SLE causes kidney inflammation (swelling or scarring) of the small blood vessels that filter wastes in your kidney (glomeruli).9

LN can lead to end-stage kidney disease, which requires kidney dialysis or a transplant. Despite improvements in both diagnosis and treatment over the last few decades, LN remains an indicator of poor prognosis for people living with lupus.10,11 Manifestations of LN include proteinuria, elevations in serum creatinine and the presence of red and white blood cells in the urine.

About GSK

GSK is a global biopharma company with a purpose to unite science, technology, and talent to get ahead of disease together. Find out more at gsk.com/company

References

[1] Kyttaris VC. Systemic lupus erythematosus: from genes to organ damage. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;662:265-83. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-800-3_13. PMID: 20824476; PMCID: PMC3153363.

[2] Mahajan A, Amelio J, Gairy K, Kaur G, Levy RA, Roth D, Bass D. Systemic lupus erythematosus, lupus nephritis and end-stage renal disease: a pragmatic review mapping disease severity and progression. Lupus. 2020 Aug;29(9):1011-1020. doi: 10.1177/0961203320932219. Epub 2020 Jun 22. PMID: 32571142; PMCID: PMC7425376.

[3] National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Lupus and Kidney Disease (Lupus Nephritis). Available at www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/kidney-disease/lupus-nephritis.

[4] Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Rahman P, et al. Accrual of organ damage over time in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2003;30(9):1955-1959.

[5] Sung YK, Hur NW, Sinskey JL, et al. Assessment of damage in Korean patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2007;34(5):987-991.

[6] Segura BT, Bernstein BS, McDonnell T, et al. Damage accrual and mortality over long-term follow-up in 300 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in a multi-ethnic British cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020;59(3):524-533.

[7] Lopez R, Davidson JE, Beeby MD, et al. Lupus disease activity and the risk of subsequent organ damage and mortality in a large lupus cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51(3):491-498.

[8] van Vollenhoven R, Askanase AD, Bomback AS, et al Conceptual framework for defining disease modification in systemic lupus erythematosus: a call for formal criteria Lupus Science & Medicine 2022;9:e000634. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2021-000634.

[9] National Kidney Foundation, Lupus and Kidney Disease (Lupus Nephritis). Available at www.kidney.org/atoz/content/lupus

[10] Gordon C, Hayne D, Pusey C, et al. European Consensus Statement on the Terminology used in the Management of Lupus Glomerulonephritis. Lupus 2009;18:257-26.

[11] Waldman M and Appel GB. Update of the Treatment of Lupus Nephritis. Kidney International 2006;70:1403-1412.

Survey results infographic

Download the survey results infographic